THIS MONTH IN ENGINEERING | July 1865, The River, the Engineer, and the Ghost of Cholera

- Rebeka Zubac

- Jul 28, 2025

- 2 min read

Before London had a proper sewer system, the city was breathing through its throat. The Thames, once a trading artery, had become an open drain. It was bloated with human waste, industrial runoff, and the debris of a city growing faster than it could reason with. By the summer of 1858, the stench was so oppressive that Parliament considered relocating. Curtains at the Palace of Westminster were soaked in chloride of lime. There was nowhere left to look away.

And so, into this moment stepped an engineer with no taste for politics and even less for showmanship. His name was Joseph Bazalgette.

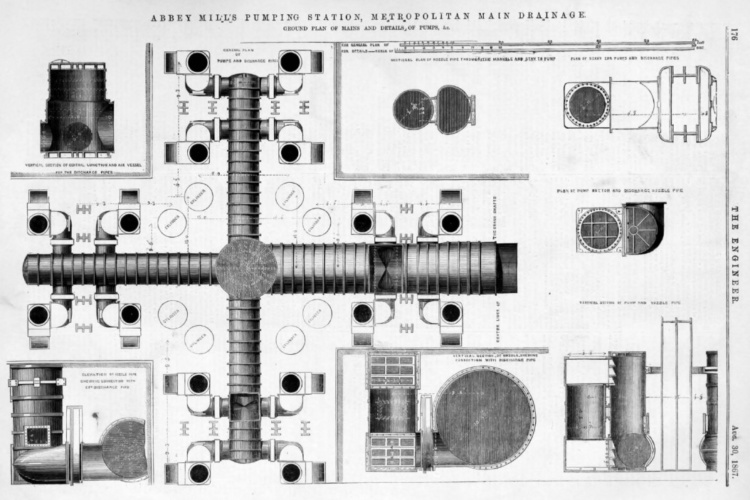

What Bazalgette proposed was not just large. It was unprecedented. He designed 1,300 miles of brick sewers, 82 miles of intercepting tunnels, four pumping stations, and an entirely rethought relationship between a city and its waste. But scale was not his boldest idea. It was restraint. He calculated the pipe sizes based on generous projections for London’s most densely populated neighbourhoods, then doubled them. Not because he had to, but because, as he said, “we're only going to do this once, and there's always the unforeseen.”

His system did not just redirect sewage. It redefined urban public health. Cholera, typhoid, and dysentery began to disappear. The Thames, long derided as the most polluted river in the world, began its slow return to life. And the embankments that concealed his infrastructure became part of London’s civic identity. A city that had once tried to flee its own river was now built around it.

Today, parts of Bazalgette’s original system remain in use. But his legacy is under pressure. In response to storm overflows, London is building the £4.2 billion Thames Tideway Tunnel, a new super sewer that builds upon the old. Its advocates see foresight. Critics call it a solution to a problem better solved with smarter, decentralised systems. The debate echoes Bazalgette’s own century and reminds us that the measure of good engineering is not always its visibility, but its longevity.

Bazalgette once said the goal was to divert the cause of the mischief to a locality where it can do no mischief. In doing so, he did not just chain the river. He freed the city.

What do we leave behind when we get it right and no one notices?

—

🔗 Source:

The Guardian | The Engineer | Halliday, The Great Stink of London (1999) | Allen, Cleansing the City (2008) | Mayhew, London Characters and Crooks (1996)

Photos:

Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891) | Sir J.Bazalgette inspects a sewer | Image from June 1858 showing Bazalgette's London sewer plans | Engineering drawing of the Abbey Mills pumping station

#ThisMonthInEngineering #JosephBazalgette #HydraulicDesign #EngineeringLegacy #GoldfishAndBay #ThamesTideway #PublicHealthEngineering